Aviation professionals in Florida and The Bahamas have had to deal with some of the world’s most extreme weather in recent years to keep operations moving.

The aviation industry has always been vulnerable to extreme weather events. But with extreme weather becoming far more common, the challenges in maintaining standards in service delivery are increasing, leaving many asking if the industry is resilient enough to deal with the potential future effects of climate change.

Back in 2017 Hurricane Irma and last year Hurricane Dorian left trails of destruction and devastation across the Caribbean and the Bahamas that the rest of the world witnessed in horror. But with hurricanes being one of the most frequent natural disasters to impact this part of the world, FBOs at these destinations are becoming well-practiced in hurricane planning and recovery. However, dealing with a hurricane is still an exceptionally challenging situation.

According to Jose Cabrera, station manager at Signature Flight Support West Palm Beach, Florida, the challenges for operators start long before the hurricane makes landfall. “Hurricane tracks are reviewed religiously. It is common to have multiple locations on alert, only to have the path shift with short notice,” he says.

Deborah Aharon, CEO at the Provo Air Center in the Turks and Caicos Islands was working when Hurricane Irma hit the Islands in 2017. She says, “In advance of a storm, the big concern is getting to the customer quickly enough to remove them from harm. Customers will often have a wait and see attitude, hoping a storm will change course.

“Then at the eleventh hour, they call for a plane and expect it to be readily available, but by then a number of things have changed. Airports may be closing early in order to let their staff go home to make storm preparations, commercial flights may already have canceled, increasing the demand for charter flights.”

Cabrera agrees, “Prior to a hurricane’s arrival, there is typically a mass exodus of private aircraft. Ramps become very busy. Compounding the elevated amounts of flight activity, fuel scarcity becomes a significant concern as fuel transportation providers want to move their trucks and drivers out of the way of the storm.”

Damage and debris

After the storm there is a whole new set of challenges to navigate. Runways are often left in a bad way after a hurricane has run its course. Cabrera says, “Hurricanes leave significant amounts of Foreign Object Debris over the runway. Due to the inherent value of runway and taxiway infrastructure to support hurricane relief efforts, the expeditious removal of debris is not only an airport priority, but likely of strategic significance to municipalities and even national governments.

“Lightning may cause holes in the asphalt/concrete base and water intrusion can also be significant, especially in low lying airports with poor drainage. This was particularly problematic at many airports in the Bahamas following Hurricane Dorian,” he adds.

“Fortunately, our runway doesn’t have flooding problems,” says Aharon. “Our commercial airport does – sections of the apron, the building and even the road to the airport can be underwater after catastrophic rainfall. But since our runway remains clear, as well as our ramp, we could technically operate as soon as the rain stops.”

Unfortunately, there’s no quick fix for regularly flooded runways as Cabera explains, “There is little that can be done to remediate airport geography.”

Power and communications

Another issue for FBOs in the path of a hurricane is the damage caused to power lines.

“One issue that surprised us very much was the delay in getting power restored to our fuel farm and FBO. The power company hastened to restore power to the airport but had our facilities far down on their priorities list. Yet, our facility was key for handling the relief and evacuation flights, and we also fuel most of the commercial flights at the airport,” says Aharon.

“It seemed to us that the airport authority and power company should have recognized our role and given us far greater priority.

“Underground fibre for internet made all the difference to us with our last hurricane, as we were able to remain online throughout the storm and afterwards. We didn’t expect cellphone towers to go down, as it hadn’t happened before, but they did this time and we were completely without local communication for the first several days,”

Cabrera says, “Signature San Juan in Puerto Rico experienced significant damage to the facility during Hurricane Maria. Municipal power was out, requiring the airport and FBO to operate without electricity for several days, resulting in daylight only arrivals and departures.”

Hurricane tracking

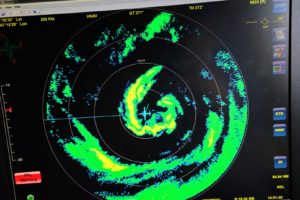

While most aviation companies do everything they can to avoid crossing the path of a hurricane, there are some men and women who hunt hurricanes and fly straight into the eye of the storm in the name of research.

Jonathan Shannon, public affairs specialist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Office of Marine and Aviation Operations says, “Our Aircraft Operations Center provides a range of airborne environmental data collection capabilities vital to understanding the Earth, conserving and managing coastal and marine resources, and protecting lives and property.

“To support hurricane operations, we can operate our three Hurricane Hunter aircraft around the clock depending on mission tasking. Our aircraft can be tasked with either research missions or reconnaissance missions.

“Notably during this season, our aircraft provided extensive coverage of Hurricane Dorian. We flew missions on it from when it was first a tropical disturbance through development into a hurricane, from Category 1 through Category 5 and back to Category 1 at landfall. During Dorian, our aircraft flew 25 missions, 10 G-IV and 15 P-3 flights, with more than 75 hours for the G-IV and 110+ hours for the P-3.”

Lessons for the future

Reflecting on 2017’s Hurricane Irma, Aharon says, “Irma taught me several things. On an immediate basis, it taught me that I could endure discomfort with far more patience than I would have anticipated. For nearly three weeks, I lived in my office because my house was uninhabitable.

“There were about 25 of us camping out, including staff and their children, a newborn baby, and a woman about to give birth to twins any minute, along with various military and relief personnel. There was only one shower, a design mistake for which I chastised myself every morning.

“The experience taught me that I could be more resourceful than I imagined. While my staff handled flight after flight, I stayed in my office tracking down supplies and making trade deals to make sure we had enough food and water.

“Later, Irma also taught me humility. I felt that I had done everything I could to prepare for the storm. It wasn’t until months later when I met my colleagues from the Pazos FBO in San Juan at a trade show and heard their story that I realized how little I had really accomplished.”

The Pazos FBO at the Luis Muñoz Marin International Airport in Puerto Rico, which was acquired and rebranded as Jet Aviation San Juan in April 2017, suffered significant damage during Hurricane Maria in 2017, including the destruction of one of its hangars. The team was able to resume operations and was the only functioning FBO at the Luis Muñoz Marin International Airport 24 hours after Hurricane Maria had hit.

According to Aharon, the team at the FBO had a written plan to deal with the hurricane, including a route map for their staff showing the various routes to the FBO. After the storm they circled the airport in a van through several check points to meet staff who were struggling to get to work. They also identified local restaurants with generators and negotiated contracts in advance to have food and water delivered daily.

“Pazos, to me, is an absolute success story in how to survive a catastrophic event,” Aharon says. “What they did was comprehensively well thought out, each potential problem and threat was anticipated and a solution worked out in advance and shared with the staff.

“I was floored by their story and their success, and ashamed of myself for feeling that I had done enough,” concludes Aharon.

If these operators are anything to go by, it would appear that the industry is doing everything it can to plan for and deal with, whatever disasters may occur in the future.