Andrew Rushton, head of aviation at Conidia Bioscience, looks at the issues surrounding microbial contamination in fuel supplies for private jets. The phenomenon can cause costly damage and failures – but why is this and what can operators do to avoid it?

Microbial contamination of jet fuel is a serious issue for the aviation industry, including the private jet sector. Once it takes hold, safety becomes a real concern and urgent repairs or biocide treatment can mean extended downtime and high costs. As microbes multiply, potentially damaging biomass and corrosive acidic compounds can be generated.

Many different types of microorganisms are able to proliferate in jet fuel. In excess amount, microbial contamination can cause many problems for aircraft. The most abundant metabolites produced by microbial communities are low molecular weight organic acids. These can create pitting corrosion in wing tanks, and structural instability. In small jets, it may even result in the need for wings to be removed so that the corrosion can be cut out and the structure restored to a serviceable condition. As microorganisms grow, they form biomass (accumulation of microbial cells) and biofilms (complex formations of cells and extracellular substances), which can adversely affect several aircraft fuel wetted components such as fuel probes affecting their ability to accurately report the aircraft fuel load. Fuel Quantity Indication System failure can be catastrophic.

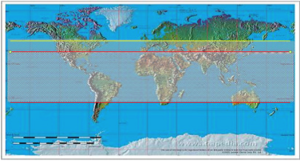

Many factors determine the level of risk of microbial contamination issues. The nature of jet fuel combined with the presence of free water creates a good environment for microbes to grow and multiply. Water is the most common contaminant in fuel systems and can lead to many problems, if uncontrolled. Water may enter the fuel or the fuel system in various ways, such as part of the refining process, as rain, as condensation in storage and aircraft tanks. The amount of water that will dissolve in any given fuel depends on both the composition and temperature of the fuel. In some systems, removal of accumulated water may be sporadic. A build-up of water in a tank can lead to increased corrosion and the potential for greater microbial activity. The amount of contamination and rate at which microbes grow will depend upon multiple factors, including temperature, volume of water in the fuel, and how long the fuel has been left in the tank. Warmer climates present higher levels of risk, as is shown in Figure 1.

The issue of microbial contamination and system damage has been amplified during the pandemic. There have been occasions where jets that have been grounded for several months, have been found to have extensive (and costly) corrosion damage when inspected prior to their return to service.

Commercial aircraft are tested periodically for fuel contamination within fuel tanks, but smaller jets may be even more susceptible to microbial contamination as they often spend longer periods on the ground, giving the microbial populations time to form and grow. Agitating fuel helps prevent water, particulates, and microbes from pooling in any part of the fuel tank, and, if a jet is in more regular use, the fuel supply is more frequently refreshed. By reducing the amount of water in the aircraft fuel tanks, the water scavenging system also provides a level of security against the accumulation and development of microorganisms which can cause operational issues, but regular testing is recommended to ensure any contamination does not go unnoticed.

A good testing regime

Testing at the tank provides jet operators with a quick, easy, and relatively low-cost method of helping to ensure that contamination is not allowed to cause damage to fuel tanks and systems. Testing frequency will depend on aircraft operating conditions and climate, but, in general, it is recommended that even with regular operation and water drain every seven to 14 days, tests to show levels of microbial growth in fuel should be carried out at least once per year and preferably every six months, especially during spring/summer as weather patterns change. If a jet is not in operation for longer periods, most OEMs recommend that water is checked and drained every seven days and testing for microbial contamination carried out every month.

Why test at the tank?

Although fuel samples can be sent to a laboratory for testing, testing at the tank offers a quicker and more accurate solution. As the microbes within the fuel are living organisms, their population can change over time and with changes to their environment. This means that any samples sent to a laboratory need to be transported quickly and under environmentally controlled conditions.

Although fuel samples can be sent to a laboratory for testing, testing at the tank offers a quicker and more accurate solution. As the microbes within the fuel are living organisms, their population can change over time and with changes to their environment. This means that any samples sent to a laboratory need to be transported quickly and under environmentally controlled conditions.

Single-use immunoassay test kits, based on the same technology as pregnancy or Covid lateral flow test kits, require no special handling or training, give results in a matter of minutes, and avoid the logistical challenges of transporting fuel samples. They provide an excellent preventative maintenance solution with accurate results and indication of contamination levels, which can be immediately shared and logged for trending purposes. Depending on results, testing intervals can be tailored to ensure a robust regime is in place to best protect the aircraft.

Fuel sampling and testing at the tank is straightforward and can be added to day-to-day operations with no special skills or training required. The test takes no more than 15 minutes to complete, and results are available immediately, enabling appropriate action to be taken straight away to help prevent corrosion or damage to aircraft fuel systems. Results can be logged and trended to optimise this simple preventative maintenance regime according to each individual aircraft’s operation and environment. Ultimately, it is a sure and simple way to help avoid the damage that microbial contamination can cause for any type of business/private jet.